Why the car is here to stay

Car-free neighborhoods have negative consequences, such as segregation and the emergence of uniform enclaves, writes Carlo van de Weijer.

Published on April 3, 2025

Carlo van de Weijer has a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the Eindhoven University of Technology and a PhD degree with honors from Graz University of Technology. He has broad experience in the automotive industry. Currently, he is the Managing Director of the Eindhoven AI System Institute (EAISI).

The car has conquered a dominant place in our lives in recent decades - and not without reason. It forms the backbone of commuting, offers indispensable flexibility, and contributes to economic mobility. People value their cars; it is their personal space, the mobile part of their home in which they feel free and independent. Car use in the Netherlands remains high, and this is not expected to change in the future.

But the space that cars occupy is a growing problem, especially in cities. That is why many cities are experimenting with low-traffic or even car-free neighborhoods. The future Utrecht neighborhood of Merwede is one such progressive experiment, where the cyclist and pedestrian are king and the car has been pushed to the margins. It offers undeniable advantages: children can play freely, the air is cleaner, and the streets look calmer and greener.

Intensive human habitation

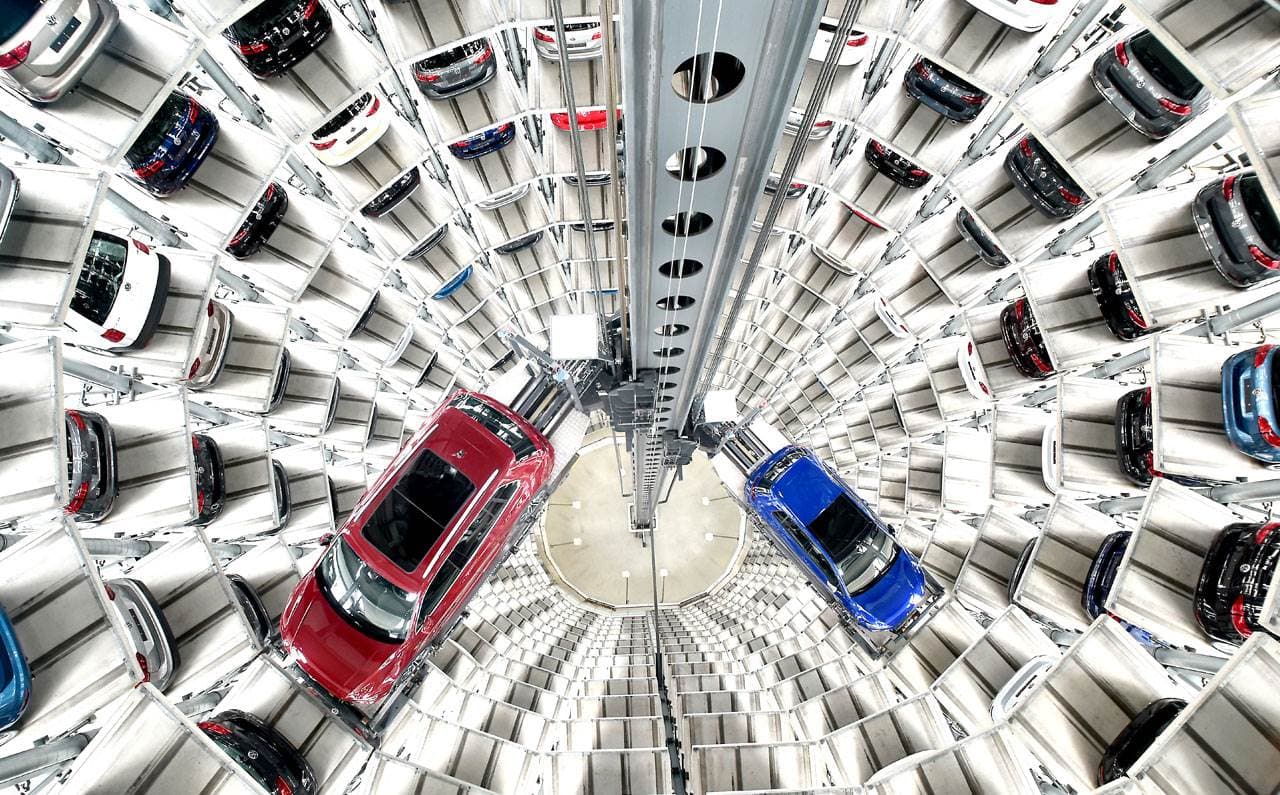

The plan for the Merwede neighborhood goes even one step further. Parking will be scarce: there will be fewer than one expensive parking space for every six homes, in garages on the outskirts of the neighborhood. The designers are therefore assuming that car ownership is more than three times lower than the already low average in Utrecht. With 40,000 people per square kilometer, the neighborhood will soon be by far the most densely populated in the Netherlands. With such intensive human habitation, it is understandable that every square meter counts and that you would prefer to exclude the space-inefficient car.

Utrecht Merwede: no cars © Landscape Architects

The neighborhood has a history of busy agriculture and later as an industrial boom area. The street names are named after all those makers and doers: The Potter, The Typesetter Square, The Bicycle Maker. But the fear is that it is precisely those makers and doers who will not feel very much at home there - in favor of highly educated, progressive city dwellers who can afford to live without a car. For a factory worker, a healthcare worker with irregular shifts, or a truck driver, a vehicle is often not a choice but a necessity. For them, a car is not a luxury, but a lifeline. Neighborhoods with a single demographic increase the risk of polarization, misunderstanding, and social isolation because people have little to no contact with other walks of life. This can lead to a monotonous, vulnerable environment with single-faceted facilities and crumbling social cohesion.

A world of academics

For the Merwede neighborhood, the focus is on shared cars and nearby public transportation, but in practice, these will offer little solace. For decades, policy reports have outlined a future in which the car would become obsolete, replaced by shared mobility and multimodal transportation. This vision seems to originate mainly from a world of academics and urban planners, who themselves function perfectly well without a car.

Utrecht is not exactly looking forward to a second Uithof line disaster project - such a tram will mainly be at the expense of people on bicycles. What we can be sure of is that there will undoubtedly be a lot of cycling in the Merwede neighborhood – not only by residents, but also by a constant stream of delivery bicycles and autonomous carts. After all, a neighborhood with few cars is a paradise for home delivery services of all kinds of goods and services.

Utrecht Merwede: no cars © Landscape Architects

Few visitors

There will be a lot of interest in the neighborhood given the continuing housing shortage and the fact that Utrecht has plenty of hipsters, expats, and older people who want to live without many friends (after all, you don't get many visitors). In practice, the relatively high proportion of social housing will benefit highly educated part-time workers more than the intended lower income groups. I fear it will not be a very diverse or child-friendly neighborhood.

If the trend towards the cities were to decrease again – it has happened before – or the housing market were to cool down, a problem could arise with the saleability of these homes. Hopefully, there will still be room for a few extra parking garages, and the municipality will realize that they should be partially subsidized, just as car sharing and public transportation also require subsidies.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the neighborhood is trying to anticipate the mobility issue of the future: scarce space. In urban areas, cars will have to disappear from view more than ever. Out of sight, but not out of society. The car is too functional, too efficient, too affordable and too essential for that to happen, preventing neighborhoods from turning into uniform enclaves.

So hide the car, but don't chase it away.

This column was first published in FD. Read the full article here (in Dutch).