World-Class Industry? Only with a World-Class Society

Those who focus solely on “earning capacity” risk losing society along the way, Tilburg University warns.

Published on December 20, 2025

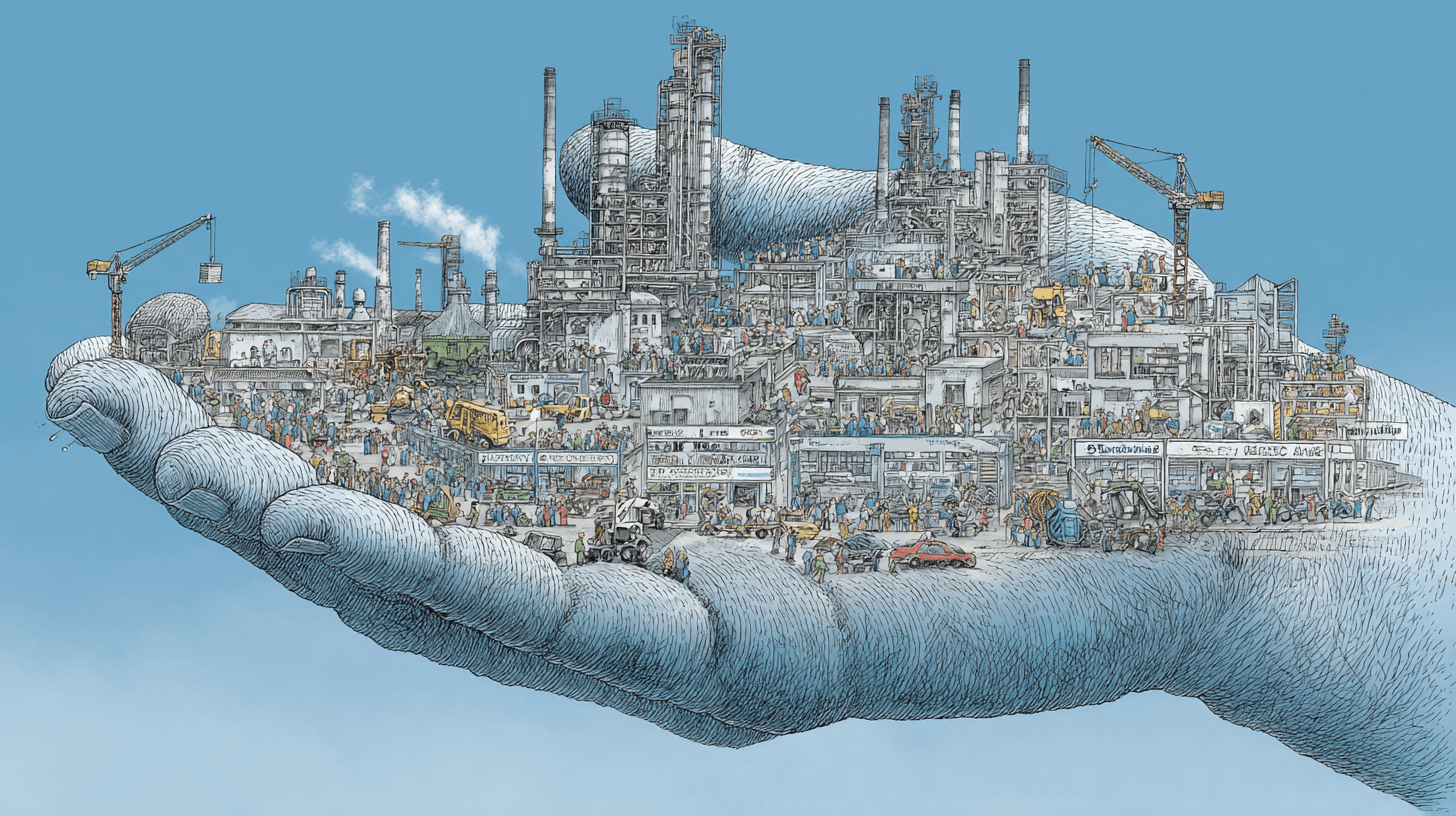

World Class Industry is supported by a World Class Society.

Bart, co-founder of Media52 and Professor of Journalism oversees IO+, events, and Laio. A journalist at heart, he keeps writing as many stories as possible.

Economic growth, technological innovation, and competitiveness dominate the political debate in Europe and the Netherlands. But anyone who focuses exclusively on “earning capacity” risks losing society itself. That is the warning issued by Tilburg University researchers Ton Wilthagen and Lex Meijdam in a new position paper, which offers a sharp alternative to the thinking of Mario Draghi and Peter Wennink.

Europe stands at a crossroads. The message from former ECB president Mario Draghi is clear: without significant investments in technology, industry, and productivity, Europe will lose its economic and geopolitical position. In the Netherlands, former ASML CEO Peter Wennink translated that call into an equally alarming report on the country’s earning capacity. Growth is essential, he argues; without it, healthcare, security, and social security will become unaffordable.

According to Tilburg University, however, a crucial element is missing from this debate: society itself. In the position paper published this week, World Class Industry, World Class Society, the Tilburg researchers argue for a fundamentally different approach. Economic strength and broad prosperity, they contend, are not sequential goals but must be developed simultaneously and in close interconnection.

No industry without society

The paper’s core proposition is as simple as it is sharp: there can be no world-class industry without a world-class society—and vice versa. According to the authors, both Draghi and Wennink primarily focus on economic growth, productivity, and strategic autonomy. That focus is understandable, given geopolitical tensions and competition with the United States and China. But it is also risky.

“In these visions, people and their lived environment are not central,” the researchers observe. Social equality, living conditions, health, and social cohesion are addressed, but primarily as by-products of economic growth. This reflects a classic “trickle-down” assumption: if companies thrive, society will ultimately benefit.

Tilburg University argues that this reasoning is becoming increasingly challenging to sustain scientifically. Rapid economic and technological growth can actually lead to greater inequality, polarization, and a loss of public support for innovation. Silicon Valley serves as a cautionary example: technologically leading, yet deeply divided socially.

Broad prosperity as a compass

The alternative proposed by Tilburg University is to think in terms of broad prosperity. This means looking beyond GDP growth alone, to everything that has value: job security, health, education, the living environment, social connectedness, and ecological sustainability—now and for future generations.

Economic growth remains vital in this framework, the authors emphasize. But it is not an end in itself. Growth must take place under clear conditions—what economist Mariana Mazzucato calls “conditionalities”—so that technological progress genuinely contributes to social progress.

This requires different choices in innovation policy. Mission-driven innovation, focused on societal challenges such as healthcare, climate, energy, and digitalization, offers the best prospects for sustainable growth, according to the paper. That also means explicitly examining who benefits from innovation—and who does not.

Brainport as a mirror

© IO+, source ‘World Class Industry, World Class Society’, Tilburg University (december 2025)

The Brainport region around Eindhoven serves as a concrete case study in the paper. Economically and technologically, the region is among the global top tier, with ASML as its flagship. At the same time, research shows that about 13 percent of its residents score poorly on multiple broad-prosperity indicators. That amounts to roughly 100,000 people - “three sold-out PSV stadiums,” as the authors put it.

This illustrates their point: high average prosperity can coexist with persistent disadvantages. Policymaking that focuses solely on economic growth risks overlooking these structural inequalities.

From triple helix to multiple helix

Tilburg University, therefore, calls for a broadening of innovation and industrial policy. Not only governments, businesses, and knowledge institutions (the familiar triple helix), but also trade unions, civil society organizations, and citizens should be structurally involved. Technology policy must be socially inclusive, and investments in AI, energy, and defense should go hand in hand with investments in education, healthcare, housing, and social infrastructure.

Concrete proposals are not lacking. The paper advocates, among other things, a “Broad Prosperity Impact Scan” for major investment decisions, better use of Statistics Netherlands (CBS) indicators in policymaking, and a stronger regional spread of innovation programs beyond the Randstad.

More than a footnote

The position paper explicitly does not reject Draghi or Wennink. According to Tilburg University, their analyses are valuable and urgent. But without an explicit societal agenda, their economic prescriptions risk becoming one-sided.

The call is therefore clear: if Europe and the Netherlands truly want to be future-proof, a “World Class Industry” alone will not suffice. Only by developing the economy, technology, and society in sync can broad prosperity be safeguarded.

Or, as the paper succinctly puts it, earning capacity is not a condition alongside people and planet; it is an integral part of them.