Bart, co-founder of Media52 and Professor of Journalism oversees IO+, events, and Laio. A journalist at heart, he keeps writing as many stories as possible.

When Thomas Spencer saw the invitation to speak at the first Watt Matters in AI conference, he didn’t hesitate. “The energy industry needs to understand more about compute,” the Senior Energy Analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA) told the audience. “We don’t really understand it very well. And if computing becomes a larger and larger source of energy demand, then we'd better understand it better.”

It was a moment of disarming honesty, and it set the tone for a talk that revealed an uncomfortable truth: the world is building the backbone of the AI era on an energy system that barely grasps what’s coming.

External Content

This content is from youtube. To protect your privacy, it'ts not loaded until you accept.

The hidden giant: data centers as the real face of AI energy demand

Spencer started not with AI, but with the physical places where AI actually lives: data centers.

“When we talk about the energy consumption of AI today, we are essentially talking about the energy consumption of data centers,” he said.

Three characteristics make data centers unlike any other energy-intensive infrastructure:

1. They cluster, and in the wrong places: IEA’s geospatial mapping of 11,000 data centers shows tight clusters near major cities. Historically, this was about latency. But today it creates a new problem: AI compute is piling onto grids that are already congested.

2. They are getting massive: Five years ago, 100 MW was large. Now? 2 GW facilities are under construction, 5 GW projects have been announced, and a modern data center can consume as much electricity as 2 million households. For context, an aluminium smelter - long the poster child of “big power users” - sits at about 750 MW, Spencer said.

3. They are built much faster than the grids that must feed them: A hyperscale data center can move from idea to operation in 2-3 years. A transmission line to power it? 4-8 years in advanced economies. This mismatch alone explains much of the strain grid operators face today.

Watt Matters in AI

Read all our stories around the Watt Matters in AI conference here. This list is regularly updated

Zooming out: globally big, locally disruptive

In global numbers, data centers don’t yet dominate: 415 TWh in 2024, growing to ~950 TWh by 2030, rising from 1.5% to about 3% of global electricity consumption. But the local story is wildly different.

In emerging economies, data centers will account for <10% of electricity demand growth. In the United States, which houses 45% of global capacity? “By 2030, data centers will consume more electricity than all energy-intensive industries combined: steel, chemicals, cement, aluminium,” Spencer said. “Every time I repeat it, I don’t quite believe it. But it’s true.”

It is one of the clearest signals that AI is reshaping the energy landscape faster than any previous digital wave.

The projection problem: “We’re flying blind”

Spencer displayed a startling chart: recent studies of data center electricity use, even for historical years, differ by orders of magnitude. The reason? A fundamental lack of data and no standardized methodologies. “There’s a lot of hype and confusion about the energy consumption of AI,” he said. “And the energy sector lacks the data to clarify it.”

IEA’s own approach - modeling based on global shipments of servers, storage, and networking equipment - is constrained by the data available and by the physical limits of global chip manufacturing.

To get beyond guesswork, Spencer is convinced that the energy sector must understand actual compute demand, not just server shipments, chip-level efficiency trajectories, and software and model-level efficiency gains or regressions. Today, almost none of that data exists in a form energy modelers can use.

Scenarios in the fog

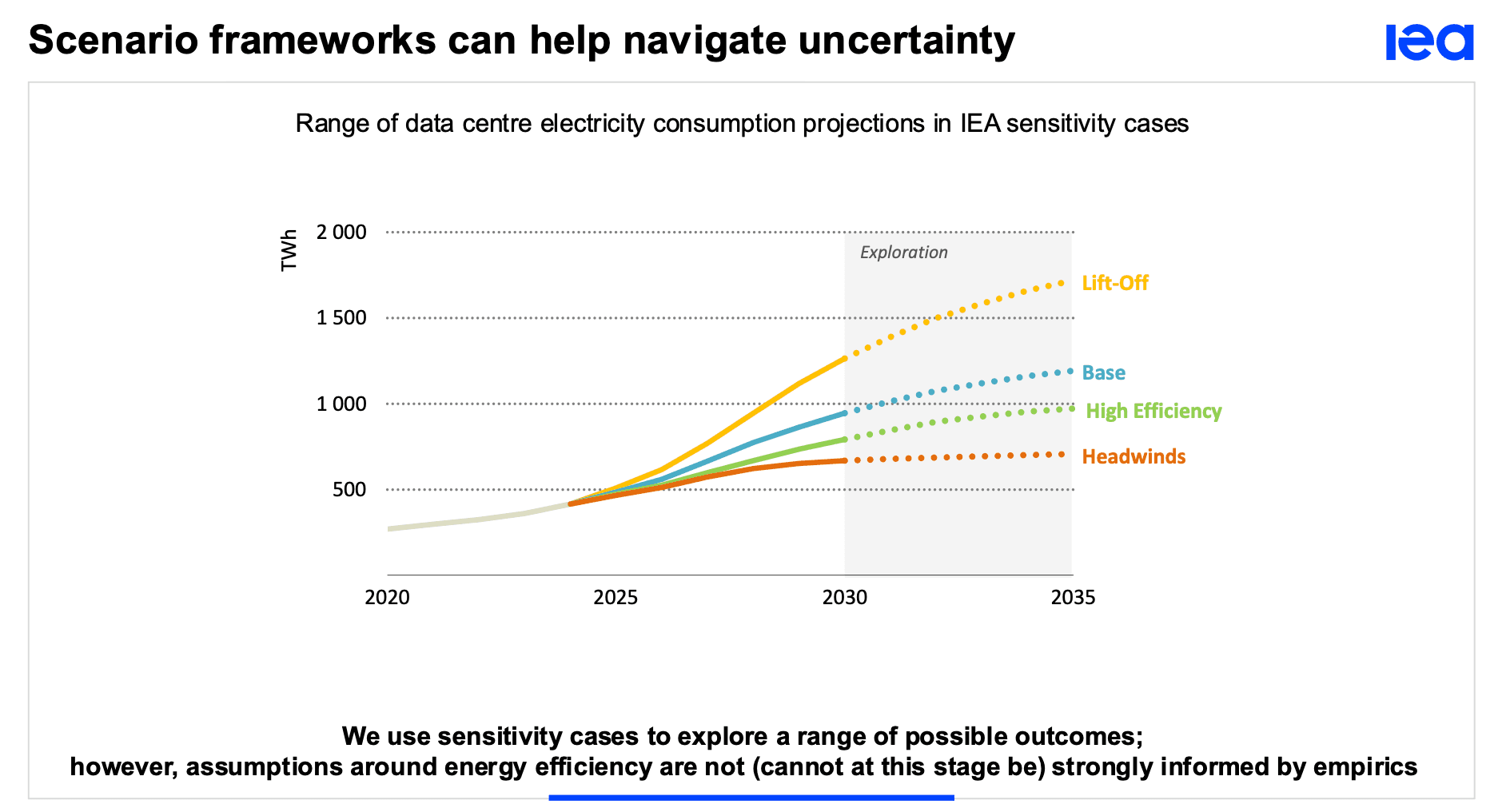

Given the uncertainty, the IEA presented four scenarios:

- Base Case: Data center consumption doubles by 2030.

- Liftoff Case: An unconstrained upper bound - assuming no bottlenecks in grid capacity or chip supply. Spencer called this one “less probable,” but useful as a guardrail.

- Headwinds Case: A slowdown triggered by financial doubts around AI ROI. Even here, consumption doesn’t fall, it just grows more slowly. Notably, global data center investment in 2025 will hit $580 billion, surpassing global oil supply investment for the first time in history.

- High Efficiency Case: The most hopeful, and the least credible.

“It was essentially impossible to calibrate,” Spencer admitted. “We simply don’t have the data to understand the efficiency trajectory of compute, whether from hardware, software, or new paradigms like neuromorphic or photonic computing.” This gap is why he called for far more dialogue between the compute world and the energy world.

The supply chain threat nobody is talking about

Beyond electricity, AI computation will reshape global materials demand.

By 2030, data centers could add 2% to global copper demand, in a world where the IEA forecasts a 30% demand-supply gap by 2035. Gallium, critical for next-generation power electronics, is already 99% refined in China. LFP batteries for backup power introduce additional geopolitical dependencies. “As we think about innovation trajectories for compute, supply chain security must be part of the conversation.”

Thomas Spencer, IEA at Watt Matters in AI

Spencer ended with a slide that looked almost embarrassingly simple: "activity × intensity = energy consumption." For steel, it works beautifully. For transport, also fine. For compute? Not so much.

The energy world just doesn’t know what the real societal demand for compute will be, how efficient future chips will become, how fast model-level efficiency will evolve, or what workloads will move to the edge, and which will remain centralized. "Our projections are necessarily short-term,” he said. “We are missing the upstream assumptions that would let us look further out.”

And so he came to the Eindhoven conference with a request, not a warning. “This is a plea for more conversations between my community and your community.”

The bottom line: AI’s energy future isn’t scary, it’s uncertain

Spencer pushed back against the most sensational claims about AI consuming "all the world’s energy." IEA sees strong growth, but not an energy apocalypse. What is alarming is the uncertainty: fast-scaling compute, slow-scaling grids, opaque data, fragile supply chains, and exploding local impacts.

AI isn’t breaking the energy system yet. But it is revealing that the world’s energy planners are missing critical visibility into what is now one of the fastest-growing industrial sectors on the planet. “If compute is going to be a major driver of energy demand, then we need to understand it much better than we do today.”