Hydrogen 2025: The hard landing of a promise

A look back at the hydrogen year 2025 reveals a sector in dire straits.

Published on December 29, 2025

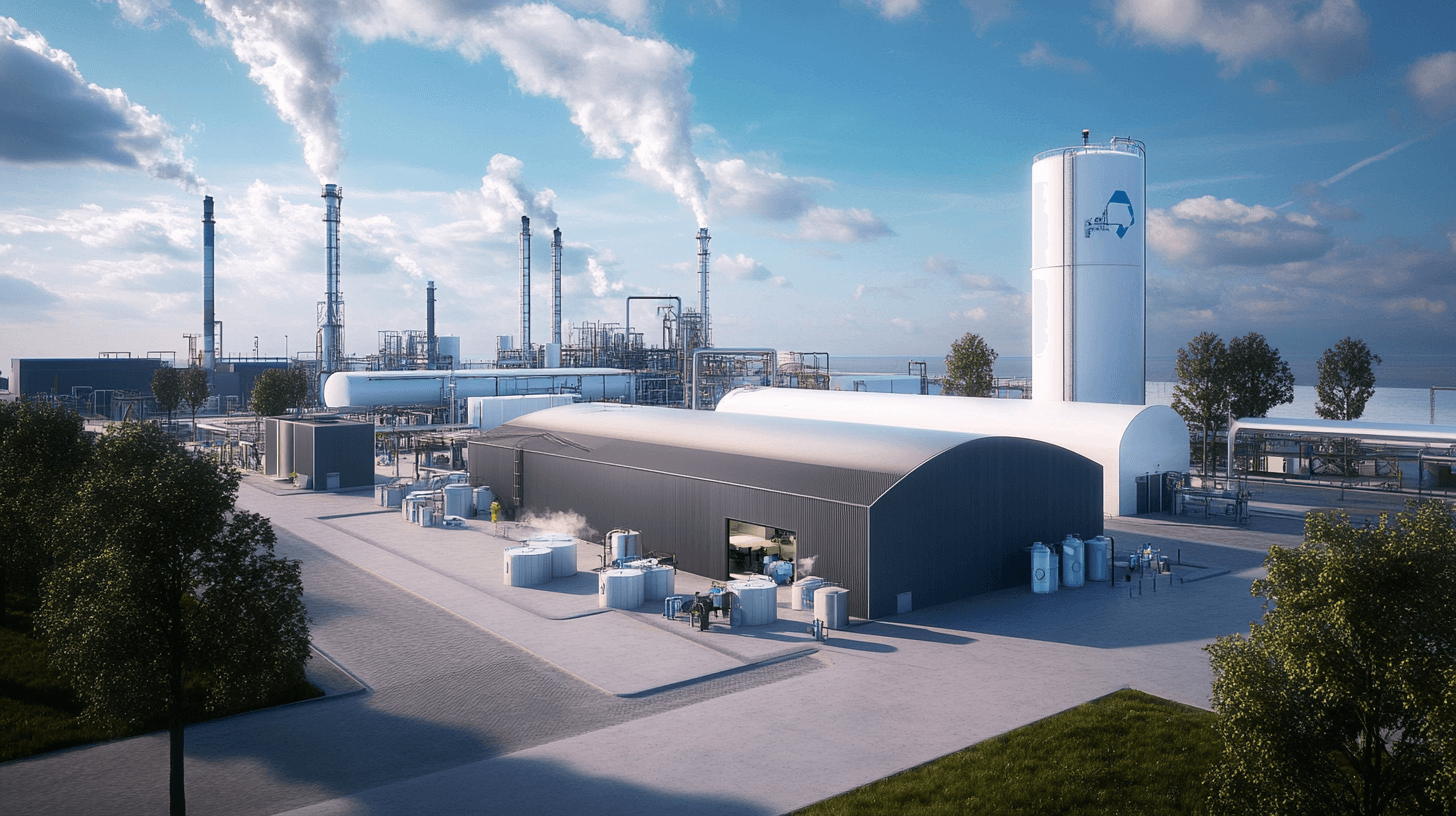

AI-generated image

Team IO+ selects and features the most important news stories on innovation and technology, carefully curated by our editors.

Anyone who read the policy documents in 2020 saw a future in which hydrogen would become the lubricant of the entire economy. It was a time of grand visions in which the ‘hydrogen ladder’ was widely used. Now, five years later, the honeymoon phase is definitely over. 2025 does not mark the year of the big breakthrough, but the year in which economic and physical laws have overtaken political ambitions. Market validation is harsh: projects are delayed, the infrastructure is struggling with enormous funding shortfalls, and for consumers, the door to hydrogen mobility has definitively slammed shut. This is not an obituary for an energy carrier, but a necessary market correction. We are seeing a shift from broad dreams to a narrow and strategic focus, where the question is no longer ‘what can we do with hydrogen?’, but ‘how do we pay for the necessary infrastructure for the few sectors that cannot do without it?’.

The billion-dollar infrastructure puzzle

The backbone of the Dutch hydrogen ambition, the national transport network, is creaking under financial pressure. Whereas Gasunie and the government initially assumed a manageable start-up phase, the reality in 2025 is proving to be stubborn. A recent report by the Netherlands Court of Audit reveals a painful funding gap of €1.8 billion. The expected start-up losses have exploded to €2.5 billion, more than three times the reserved subsidy pot of €750 million. This miscalculation is not just an accounting problem; it threatens the Netherlands' strategic position as the energy hub of Northwest Europe.

The causes are diverse, but boil down to a classic overestimation of the rollout speed and an underestimation of construction costs. The original goal of having a transport capacity of 4 gigawatts (GW) operational by 2030 has now been adjusted to 2032. At present, only one part of the network, around Rotterdam, is actually under construction. The feasibility of the other fourteen routes is still being investigated, with the requirement that 25% of the capacity must be contracted in advance hanging like a millstone around the necks of project developers. The delay has direct consequences for the industrial clusters in Zeeland, Limburg, and the North, which now have to recalibrate their sustainability plans on a timeline that is constantly shifting.

The supply problem: Green ambitions, gray reality

Public debate often points to a lack of demand, but this is a misconception. Industrial demand is stable and present; the problem is that it is almost entirely met by gray hydrogen, produced from natural gas. In the Netherlands, 80% of production is still gray, resulting in annual emissions of 13 million tons of CO2. The transition to green hydrogen is not stagnating due to unwillingness, but due to an acute shortage of electrolysis capacity. The target of having 4 GW of electrolysers in operation by 2030 contrasts sharply with reality: in 2025, only 0.2 GW is under construction, or 5% of the target.

In 2024, the European Court of Auditors already criticized the EU strategy to produce 10 million tons of green hydrogen as “unrealistic” and politically driven rather than practically feasible. Although the Dutch government is trying to steer the course with subsidies such as the OWE scheme — under which more than €700 million has been allocated to projects accounting for 602 MW in 2025 — the pace remains too slow. The production costs of green hydrogen remain significantly higher than those of the gray variant, and as long as that gap is not closed by economies of scale or CO2 pricing, the business case for producers remains shaky. Brussels' recent approval of nearly €1 billion in state aid is a step in the right direction, but it only closes part of the gap between ambition and realization.

Mobility: The final nail in the coffin for the passenger car

2025 will go down in history as the year that saw the definitive end of the hydrogen passenger car. For years, the technology was kept alive by companies such as Toyota and Hyundai, but the market has spoken. Stellantis, the parent company of volume brands such as Peugeot and Fiat, has halted the development of hydrogen technology for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles. This follows a broader trend in which fuel station operators such as Shell and OMV are taking their losses and closing locations; in Germany alone, 22 stations disappeared this year. In the Netherlands, the number of filling stations has remained stuck at less than 25.

The reasons are purely economic and physical. A hydrogen car costs around €70,000 to purchase, compared to €46,000 for a comparable battery electric vehicle (BEV). Even more devastating is the efficiency comparison. From source to wheel, a BEV has an efficiency of approximately 95%. With hydrogen, 20 to 40% of the energy is lost during production and another half during conversion in the car. At a time when green electricity is scarce, it is energetically irresponsible to choose this inefficient route for passenger transport. The focus is now shifting entirely to sectors where batteries fall short: heavy industry, shipping, and possibly aviation.

Future prospects: Strategic autonomy and innovation

Does this mean that the hydrogen economy has failed? Not at all. It means that the sector is maturing and leaving the teething problems of the hype phase behind. The focus is narrowing to applications where there is no electric alternative. Hydrogen remains indispensable for making high-temperature processes in industry more sustainable and as a raw material for the chemical industry. The government recognizes this and is now focusing on innovation and specific demonstration projects. With €134 million being made available through the DEI+ scheme in 2026, the focus is on technologies that can reduce costs and increase efficiency.

The strategic implications for the Netherlands and Europe are significant. If we fail to quickly build up our own green production capacity, we will simply exchange our dependence on Russian gas and oil from the Middle East for a dependence on hydrogen imports from other regions. In that light, the European Court of Auditors' criticism of the lack of a coherent import strategy is worrying. The coming years must be dominated by execution: actually building the electrolysers for which subsidies have been granted and getting the stagnating network up and running. The dream of hydrogen as a solution to everything has vanished; the need for hydrogen as a strategic raw material for our industry is more urgent than ever.