How a European dream could collide with harsh financial reality

At Gerard & Anton's Demos Pitches & Drinks, Euclyd’s Bernardo Kastrup speaks about his European ambitions and the reality of raising capital

Published on December 6, 2025

Bart, co-founder of Media52 and Professor of Journalism oversees IO+, events, and Laio. A journalist at heart, he keeps writing as many stories as possible.

In the AI Innovation Center on the High Tech Campus in Eindhoven, Bernardo Kastrup speaks with the composure of someone who has already lived several lives. Computer scientist, philosopher, ASML strategist, founder. And now, somewhat reluctantly, he admits, figurehead of Europe’s boldest attempt to reinvent AI computing from the ground up.

Euclyd, the company he founded just over a year ago, has quickly become something of a phenomenon. Backed by giants of the industry - among whom former ASML CEO Peter Wennink, legendary Intel engineer Federico Faggin, Silicon Hive's Atul Sinha, and Elastic founder Steven Schuurman - the startup emerged from complete stealth onto the European tech scene earlier this year and instantly dominated the conversation. It was not just the ambition. It was the tone: confident, technical, unashamedly big - a European company speaking with Silicon Valley amplitude.

“Yes, you can call it bragging,” Kastrup laughs. “It’s tongue-in-cheek. But we should be confident. Why would only Americans be allowed to speak with ambition?”

Yet beneath the humour sits a more profound frustration - one that sparked Euclyd’s creation.

“I looked around and asked: Who allowed this to happen?”

When generative AI exploded into public consciousness in 2023, Kastrup started scanning the European landscape. He saw world-class researchers, world-leading chip equipment, a sophisticated industrial base, and no serious attempt to build the next-generation silicon that would power future data-center AI.

“I remember looking for someone to blame,” he says. “Why is nothing happening in Europe? How did we allow that?”

The uncomfortable realization came quickly: there was no one else to blame. “Who could do something about it? People like me. People I know. So yes, I felt a responsibility.”

External Content

This content is from youtube. To protect your privacy, it'ts not loaded until you accept.

That sense of responsibility carried him into a long period of stealth. Euclyd would not announce anything until the company had proof that the idea was real; proof he and his friends could trust. “When you take money from a VC and fail, okay, that’s the business of risk,” he says. “But losing your friends’ money? That’s something else.”

For months, the small team - many of them colleagues from earlier chip ventures - worked on a fundamentally new architecture for AI inference. No GPU legacy. No repurposed gaming hardware. No shortcuts. A system built from the gate level up. The early design work even took place in Kastrup’s attic, where he had set up a simulator and spent long nights sketching microarchitectures the way others sketch ideas in a notebook.

When the test chip finally emerged, and Samsung agreed to produce it, Euclyd stepped into the light.

A European chip with world-scale ambition

Euclyd’s promise is huge: extremely energy-efficient inference, potentially one hundred times more efficient than Nvidia’s current data-center chips, achieved not through magic but through architectural sanity.

“Nvidia built for video games,” Kastrup says. “When large language models arrived, they were simply in the right place at the right time. But pretending a neural network is a video game with a global variable space… that’s just about the worst thing you can do for efficiency.”

Euclyd’s architecture does the opposite: no reuse of off-the-shelf IP, no reliance on generic bus architectures. Everything is specialized, deeply pipelined, built for neural inference first. The test chip contains 64 processors; the product version will scale to 16,384.

In a world of incremental optimization, Euclyd is trying the 'forbidden move': starting over.

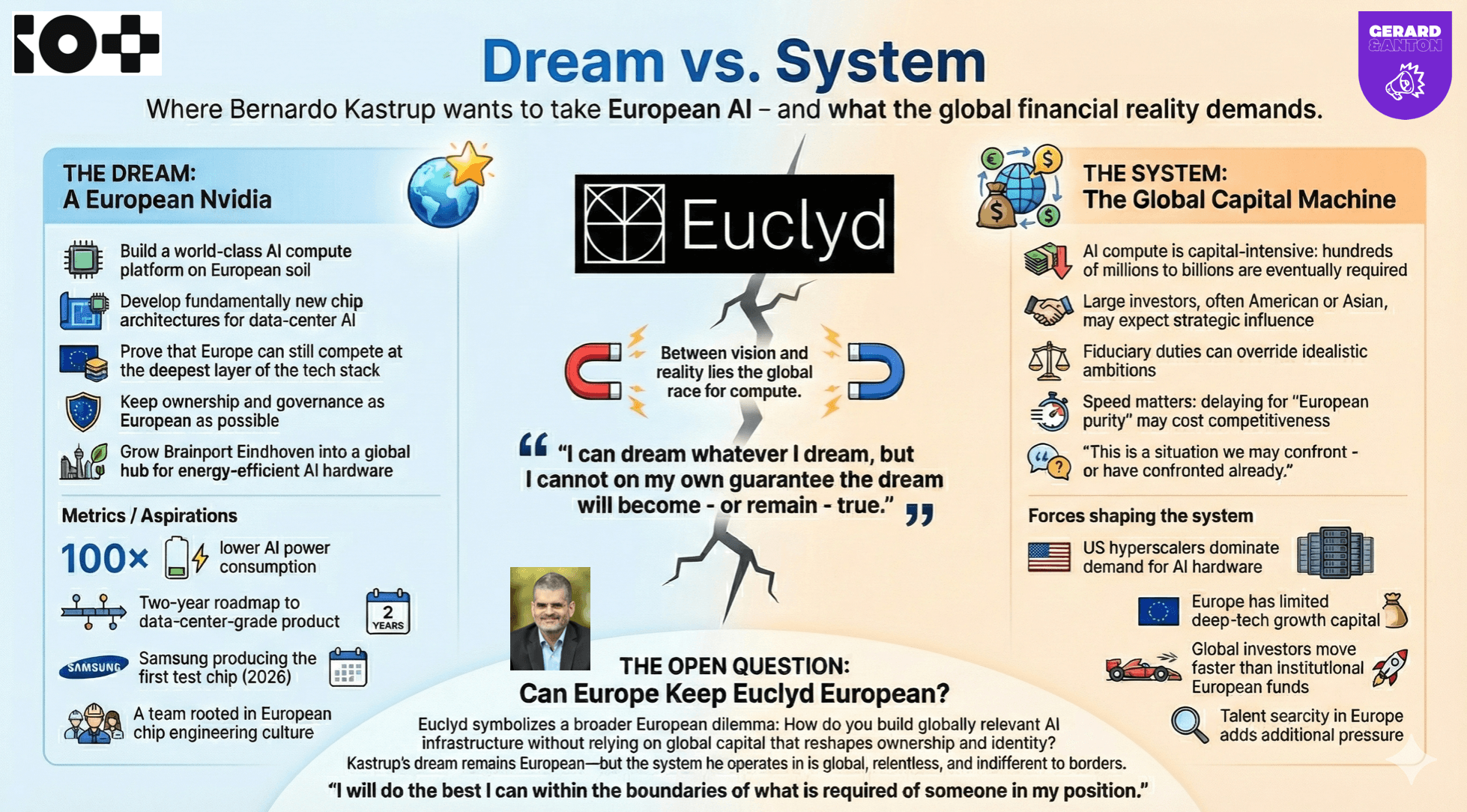

The dream: a European Nvidia. The reality: global capital

And yet, for all the technical bravado, there is one topic that makes Kastrup slow down, choose his words carefully, and speak not as an engineer but as a founder navigating forces bigger than himself.

The money.

Euclyd is raising a major financing round. And with that round comes the possibility- perhaps even the likelihood - that the company will no longer be “purely European.”

“The original dream was to do AI in Europe,” he says quietly. “To have Europe play in that space. But when you have a business, and you are spending other people’s money, you have fiduciary duties. You must follow business sense. And that may put us in a situation where we must act in ways that are not fully aligned with the dream.”

It is not hypothetical. It is happening now. “We are raising money,” he acknowledges. “This is a situation we may confront - or have already confronted. That is part of the game.”

He pauses. “I can dream, right? I can dream whatever I dream. But I cannot, on my own, guarantee that the dream will become, or remain, true. I do not control the world.”

It is a rare admission in a European tech landscape that often clings to idealism. Kastrup refuses to pretend the tension doesn’t exist. He wants Euclyd to be the Nvidia of Europe, built on European engineering, rooted in the Brainport ecosystem that shaped him. But he also wants the company to survive the global race for compute; one that Europe has joined late and underprepared.

If the right investors come from outside Europe, and if refusing them would threaten the company’s ability to compete, what should a founder do?

“I will do the best I can within the boundaries of what is allowed or required of someone in my position,” he says. “But I cannot control everything.”

A dream worth fighting for

Whether Euclyd will remain a European company in ownership structure is uncertain. Whether its technology will be global seems more likely every day. And whether Europe will finally have its own AI-compute champion may depend not just on Kastrup’s design brilliance, but on Europe’s own willingness to move at global speed.

Still, the dream persists. “Europe needs to play in this field,” he says. “It’s my wish too.”

And with that, Bernardo Kastrup - philosopher, engineer, founder - returns to his office, where a small test chip no larger than a fingernail sits waiting. The architecture within it could reshape AI's global energy footprint.

The question is whether Europe will still be the place where that future unfolds.