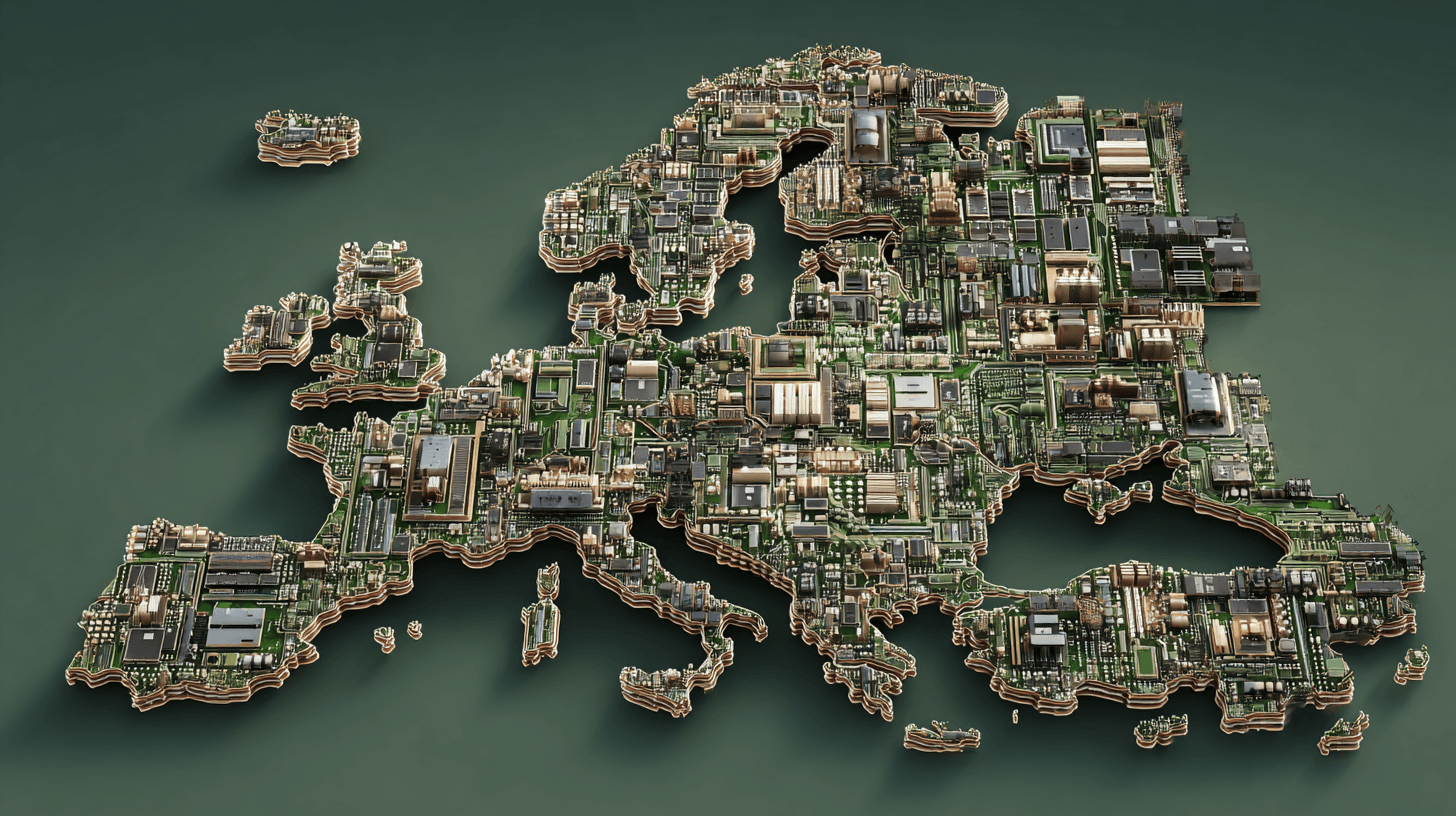

Europe’s last realistic chance in the AI race

Why Bernardo Kastrup argues that AI sovereignty will not be won in software, but in hardware

Published on January 11, 2026

Bart, co-founder of Media52 and Professor of Journalism oversees IO+, events, and Laio. A journalist at heart, he keeps writing as many stories as possible.

Europe’s position in the global AI race is often described in fatalistic terms. Advanced chips come from Asia, hyperscale AI platforms from the United States, and Europe is left to regulate, fine-tune, and hope for the best. In a long and uncompromising essay, philosopher of mind and semiconductor entrepreneur Bernardo Kastrup dismantles that narrative. His conclusion is stark but unexpectedly optimistic: Europe can still achieve AI sovereignty, but only if it abandons the illusion that software alone will save it and instead reclaims control over AI hardware itself.

Kastrup, founder and CEO of Euclyd, frames AI not merely as a technological contest but as a civilizational one. “To ensure the survival of its way of life,” he writes, “Europe must thus have the means to control the deployment of AI in its territory, so it happens on our terms.” Values such as democracy, human rights, and distribution of power, he argues, cannot be safeguarded if the core infrastructure of intelligence is imported and externally controlled.

Why AI alignment won’t be solved in software

A central claim in European AI policy circles is that sovereignty can be achieved through “aligned” European AI models—software systems trained to reflect European norms and regulations. Kastrup calls this belief fundamentally misguided. Alignment, he argues, is not an intrinsic property of models, but an emergent result of training, feedback, and context.

“Trying to address the need for alignment with homegrown software models,” he writes, “is like prescribing brain surgery to address improper education.” The analogy is deliberate: just as human values are shaped by learning rather than anatomy, AI values are shaped by training conditions rather than by the origin of the algorithm.

More importantly, training and scaling AI require enormous compute power. Without secure access to AI hardware, Europe cannot train, fine-tune, or even meaningfully control advanced systems, regardless of where the code originates. Hardware, not models, is the primary bottleneck to sovereignty.

The hidden cost of GPU dominance

Kastrup’s critique sharpens when he turns to today’s dominant AI hardware paradigm: the GPU. The global AI boom, he notes, rests on a historical accident. When transformer models emerged, they were implemented on graphics processors originally designed for video games. That serendipity propelled companies such as NVIDIA to dominance but locked the industry into a deeply inefficient architecture.

“NVIDIA’s greatest advantage,” Kastrup writes, “is also their Achilles’ heel: they are now stuck with an entire paradigm and ecosystem that is catastrophically inefficient.” GPUs treat AI workloads as if they were global, graphics-intensive problems, whereas in reality, AI relies on local, distributed data flows. The result is staggering energy waste. Data centers are already planning dedicated nuclear plants to power AI, and according to the International Energy Agency, AI data centers could consume nearly 1,000 TWh of electricity by 2030.

This inefficiency, Kastrup argues, is not a law of nature; it is a design failure.

Europe’s misunderstood disadvantage

Why, then, has Europe fallen behind? Kastrup points not to a lack of intelligence or capability, but to historical specialization. Europe’s semiconductor industry evolved around automotive needs: long product cycles, extreme reliability, and low sensitivity to chip energy consumption. Asia’s fabs, by contrast, were shaped by smartphones—short cycles, ruthless cost pressure, and relentless energy optimization.

That divergence left Europe behind at the bleeding edge of fabrication. But crucially, Kastrup argues, it did not erase Europe’s strengths in chip design. A competitive chip, he stresses, is not only defined by the manufacturing node, but by architectural intelligence. And here, Europe’s tradition of precision engineering becomes an advantage.

“AI is not videogame graphics,” Kastrup writes. Recognizing this opens the door to radically more efficient, AI-specific hardware—designed from the ground up, rather than adapted from consumer graphics.

Design as Europe’s strategic lever

At Euclyd, Kastrup claims, such a redesign yields systems up to a hundred times more efficient than current GPU-based solutions in terms of cost, energy use, and physical footprint. That efficiency margin can be used strategically: either to outperform incumbents on advanced Asian nodes, or to compensate for Europe’s manufacturing lag by producing chips locally while remaining competitive.

This is where Europe’s fragmented but formidable ecosystem comes into view. Kastrup points to advanced planar chip development at CEA-Leti, cutting-edge packaging technologies at IMEC, power electronics leadership at Infineon, AI-relevant system expertise at NXP Semiconductors, and emerging European CPUs from SiPearl.

Europe, in other words, is not empty-handed. What it lacks is coordination and ambition.

A sovereignty strategy measured in years, not decades

Kastrup’s most provocative claim is temporal: European AI hardware sovereignty, he argues, does not require thirty years. With focused investment, continent-level coordination, and a willingness to back a limited number of deep-tech players at meaningful scale, it could be achieved before 2030, at least in strategic domains such as government, defense, finance, and critical infrastructure.

These sectors, he notes, are less price-sensitive, require lower volumes, and involve the most sensitive data. Precisely where sovereignty matters most, Europe’s disadvantages matter least.

“European AI sovereignty across the entire value chain can be achieved before this decade is out,” Kastrup concludes. The alternative - continuing to depend on foreign hardware while debating alignment at the software layer - is not prudence but complacency.

Kastrup’s essay reads less like a manifesto and more like a challenge. Europe’s AI future, he argues, will not be decided by regulation alone, nor by catching up in someone else’s race. It will be decided by whether Europe dares to redesign the machine at the heart of intelligence, and reclaim agency over its own technological destiny.

Europe's last hope in the AI race | Bernardo Kastrup » IAI TV

Europe must gain AI sovereignty; here's how they can do it