Energy crisis in slow motion: 2030 goals become unachievable

Rik Thijs: “It is a failure of the national government, which should have anticipated this massive electrification a long time ago.”

Published on June 25, 2025

Bart, co-founder of Media52 and Professor of Journalism oversees IO+, events, and Laio. A journalist at heart, he keeps writing as many stories as possible.

It won't be a big surprise to most people, but the conclusion is no less impactful for that: the Brainport Eindhoven region is unlikely to meet the targets for generating green energy by 2030. Not even by a long shot. The obstacles are so significant that this conclusion can already be drawn five years before the deadline.

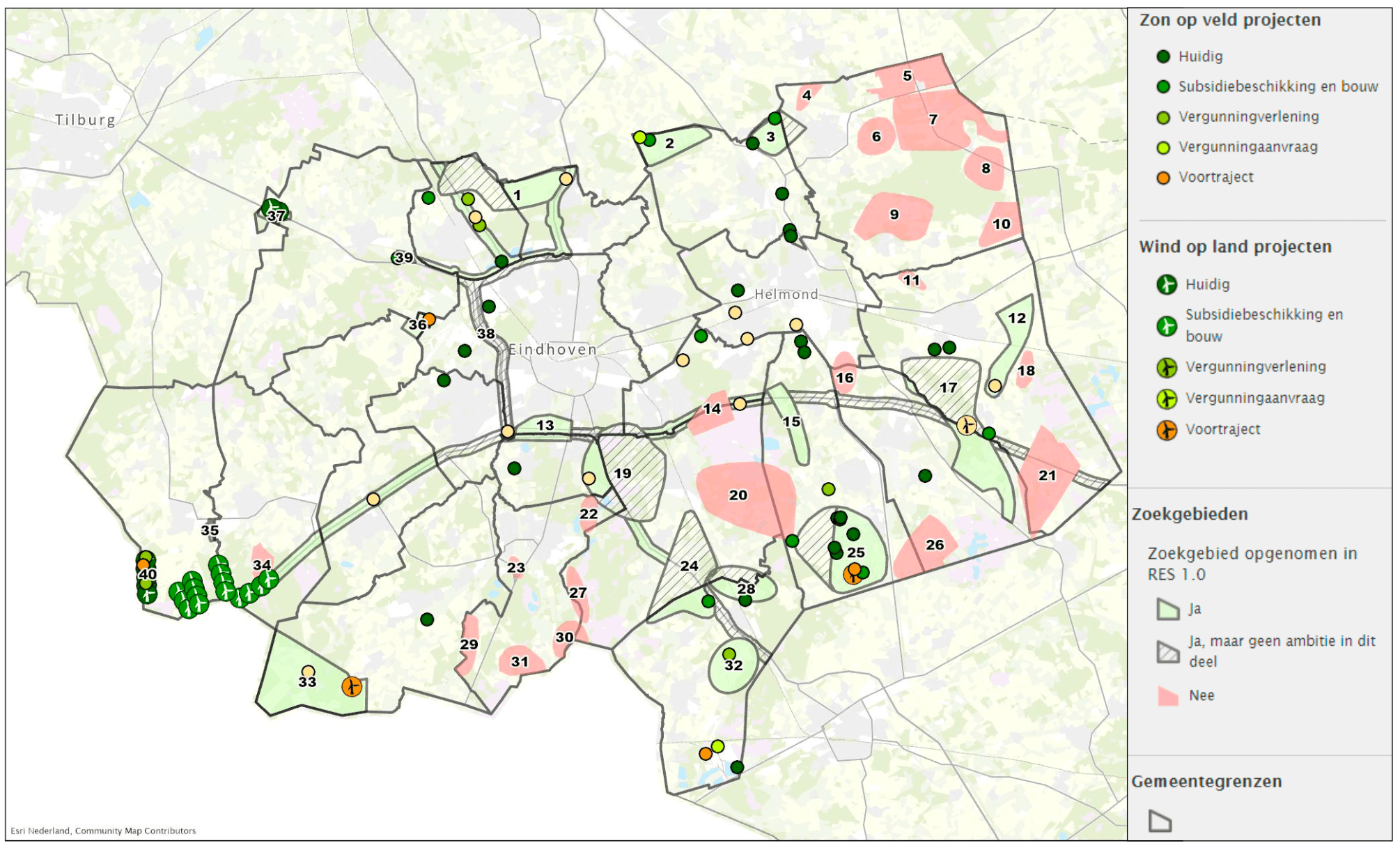

When the Regional Energy Strategy (RES) was adopted in 2021, the Eindhoven Metropolitan Region (MRE) expressed its ambition to generate two terawatt-hours (TWh) of renewable energy through solar and wind by 2030. “We were behind it then, the city councils adopted it unanimously,” says Rik Thijs, Eindhoven alderman for sustainability and chairman of the regional RES. “But by now it is clear that without drastic changes we are not going to achieve this.”

The latest progress report confirms the bleak picture. In the most optimistic scenario, the region remains stuck at 1.86 TWh. However, if uncertain projects such as the wind farms in Bergeijk and Someren do not proceed, the realistic expectation drops to 1.54 TWh. If all uncertainties are taken into account, only 1.02 TWh remains according to the official calculation rules. “In other words, we risk missing half of our target,” Thijs said.

One step forward, two backward

How did it come to this? According to Thijs, four causes play a decisive role:

- Defense and air bases: "As a region, we are surrounded by military airports. Radar detection requirements block many of the areas where wind turbines were once planned," Thijs explains. "Even small-scale wind projects like those along the A67 near Eindhoven are off the table because of this."

- Stricter rules for solar parks: In Minister De Jonge's so-called solar letter and the subsequent provincial environmental regulation, the conditions for solar energy on agricultural land were tightened considerably. "Projects that fell within the frameworks at the time have now suddenly become impossible due to changing national regulations. You change the rules halfway through the game."

- Grid congestion: The significantly increased load on the power grid is causing many projects to be put on hold. “We are not talking about minor maintenance here: 10 new high-voltage substations, 120 medium-voltage substations, 4,000 new transformer houses, and thousands of kilometers of cables are needed in our region,” Thijs lists. “One in three streets has to be opened up.”

- Declining social and political support: Protests against landscape pollution and resistance in local town councils are putting pressure on many projects. "Wind and solar farms are now visible interventions in the landscape. But doing nothing means much greater long-term damage from climate change."

Short-term wins out over long-term

It is precisely this political dynamic that worries Thijs. "To govern is to look ahead, but in the energy transition, short-term interests often win out over the necessary long-term course," he says. "Wind projects are pre-eminent subjects on which politics is easily played."

According to Thijs, there is a lack of nationally consistent policy. "This is not the fault of our residents, who are investing massively in solar panels, heat pumps, and insulation. It is a failure of the national government, which should have foreseen fifteen years ago that this enormous electrification was coming."

Not just an Eindhoven problem

Although the situation in the Eindhoven region is illustrative, the problem is widely visible nationwide. "There are regions that are better on track," Thijs acknowledges, "such as Hart van Brabant, where municipalities are jointly realizing large-scale wind projects and where revenues flow directly back into the local community. But in many regions, you see the same obstacles occurring." At the same time, the national target (35 TWh) still seems feasible.

Yet Thijs does not want to stop at this observation. "We are not throwing in the towel. Indeed, we are using these hard figures precisely to have honest conversations in our municipal councils now. What have we thrown out before that may yet need to be put back on the table?" For Rik Thijs, these are pre-eminent themes that need to be discussed everywhere in the run-up to the municipal council elections.

The region is therefore working toward a RES 2.0, which is expected to be adopted in 2027. This will examine decentralized energy systems, collective heat networks, and innovative solutions, including energy hubs, in more detail. "Hydrogen can also be given a role in this. In any case, we, as governments, must steer more actively, rather than leaving everything to the market. Only then can you also organize local support."

Support for energy transition

Thijs emphasizes that national energy policy must be structurally different. "If we do not dare to choose for the long term now, we undermine support for the energy transition itself. We ask citizens and companies to become more sustainable, but then do not provide the energy system to which they can connect."

The challenges around Eindhoven are thus exemplary for the whole of the Netherlands. Thijs: "This is the honest story: we simply need more long-term vision and national direction to make our collective climate goals at all feasible."