Becoming data objects: Bjorn Beijnon on platform power

"Big Tech platforms are apartment complexes whose residents have become data subjects.”

Published on October 27, 2025

Bart, co-founder of Media52 and Professor of Journalism oversees IO+, events, and Laio. A journalist at heart, he keeps writing as many stories as possible.

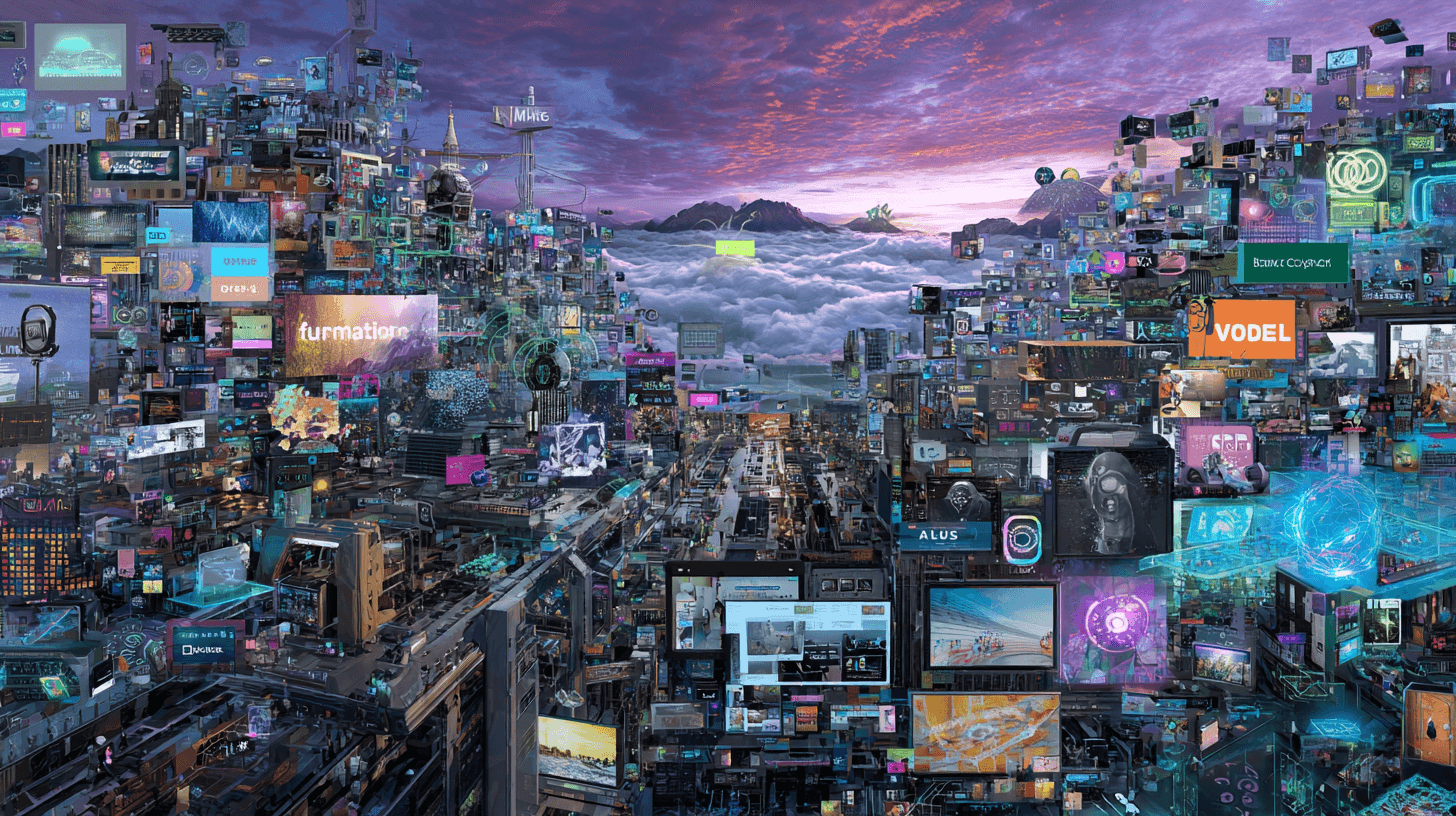

Our feeds, profiles, and recommendations don’t just reflect who we are; they shape who we become. Researcher and political candidate Bjorn Beijnon argues that platform ecosystems cultivate “data subjects” who feel in control while aligning ever more closely with Big Tech’s interests.

At the event Who Formats Our Futures?, organized by the University of Amsterdam, Dr. Rianne Riemens and Bjorn Beijnon exposed two sides of platform power: its environmental footprint and its social consequences. In a three-part short series, we unravel their messages. This is part 3. You can read part 1 here and part 2 here.

If Dr. Rianne Riemens mapped the material infrastructures of AI and energy, Bjorn Beijnon turned the spotlight on the social infrastructures of data. His talk at Who Formats Our Futures? dissected how platforms don’t merely capture information: they actively produce subjects.

“I’m interested in what we are becoming today,” Beijnon began. “Big Tech companies mold our subjectivity into a very specific format. They don’t just mirror us back, they create caricatures that we start to inhabit.”

The apartment complex of Big Tech

To explain platform ecosystems, Beijnon used a vivid metaphor. “Think of them as apartment complexes,” he said. “Alphabet owns the whole building. You can use YouTube, Chrome, Drive, Gmail, Maps, but the furniture is nailed down. You can’t rearrange it. You live by their terms and conditions.”

The aim is not just to provide services, but to capture users within a single ecosystem, maximizing data flow. “Every purchase, every stream, every click feeds into a data profile,” Beijnon noted. “And this profile doesn’t just sit there. It calls us out, it tells us: this is who you are.”

Drawing on French post-structuralist thinkers, Beijnon described how repeated recommendations and notifications act as constant hails. “LinkedIn is a perfect example,” he said. “The platform shouts at you: you’re looking for a job, you’re a professional seeking opportunities. And when you respond, you become that subject.”

He called this process interpellation: the transformation of individuals into “data subjects.”

“A data subject is someone who sees themselves as a living archive,” Beijnon explained. “They document their existence through data while still feeling in control of their choices. But the very act of feeling in control is part of the conditioning.”

Cynical participation

To test the boundaries of this subjectivity, Beijnon spent six months embedded in Dutch conspiracy communities. “These groups claim they are awake, that they resist becoming data subjects,” he said. “But what I found was a form of cynical participation. People distrust platforms, yet continue to engage with them, often reinforcing their sense of being special or ‘outside the system’.”

This led him to coin the idea of 'custom sense': a privatized form of truth shaped by personal intuition and algorithmic feedback loops. “When enough people with similar custom senses cluster, it looks like a community,” he observed. “But connectivity isn’t collectivity. It produces swarms, not publics.”

If cynicism dominates mainstream platforms, Beijnon found something different in the decentralized world of the Fediverse, a constellation of open-source platforms like Mastodon and PeerTube.

“Unlike the apartment complex of Big Tech, the Fediverse is a neighborhood of houses with different rules,” he said. “It’s built on open protocols. People there talk about commons, about collective responsibility for the infrastructure.”

The emotional tone is different too: not cynicism, but care. “There is a shared ethic of attentiveness, interdependence, and persistence in disagreement. That’s what sustains collective well-being.”

From private design to public governance

Beijnon closed with a political appeal. “Cynicism is a luxury we can’t afford; the world is burning,” he said. “We need infrastructures of care, not cynicism. And that means making platform power a matter of public governance, not just private design.”

As both a PhD researcher and a Volt parliamentary candidate, Beijnon connects theory to politics. “Transparency and open standards must become the foundation of Europe’s digital future,” he argued. “Protocols should not be owned by companies. They should be owned by people.”

“The question is simple,” he concluded. “Do we remain data subjects in the hands of platforms, or do we reclaim the power to decide what kind of collective we want to be?”